Deadly docking: The Epstein-Barr virus has long been considered a possible carcinogen. Researchers have now discovered how the virus causes our cells to deteriorate. In accordance with this, viral proteins stick to a particularly fragile spot on our chromosome 11 and cause breaks there. This, in turn, promotes the development of cancer, the team reported in Nature. The new findings now open up the opportunity to prevent this decline in a targeted way and also to identify those who are particularly at risk.

About 90 percent of us carry the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) — often unnoticed and from early childhood. However, in some cases, a pathogen belonging to the herpesviruses can make you sick: It causes glandular fever and is suspected of promoting multiple sclerosis, protracted hepatitis, and chronic fatigue syndrome. EBV is also considered a potential cause of many types of cancer, including Hodgkin’s lymphoma and nasopharyngeal cancer.

Targeting the viral protein

But how can the Epstein-Barr virus cause a cancerous tumor? Julia Su-Cho Lee at the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues may have discovered the underlying mechanism. They investigated a known property of the virus: EBV leaves behind the viral protein EBNA1 in infected cells. This binds with a kind of feedback to a specific DNA sequence in the virus’s genome, but it can also attach itself to human DNA.

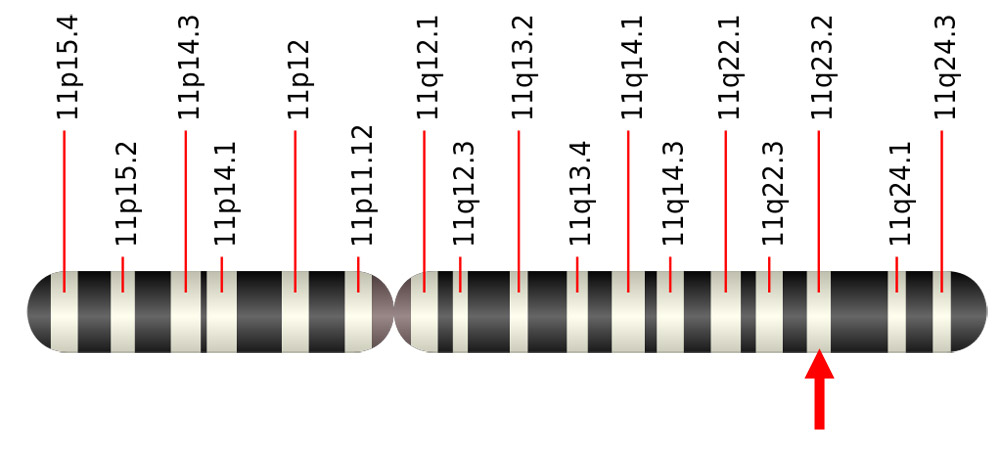

This is where Lee and her team’s study comes in: With the help of different human cell cultures, they investigated exactly where in the genome the virus protein was located. They discovered a surprising accumulation of EBNA1 proteins attached to a section of chromosome 11. More detailed analyzes revealed that the genome there contains many copies of a DNA sequence that resembles the docking sequence in the Epstein-Barr gene code. This allows the viral EBNA1 protein to attach itself to our DNA.

A fragile spot on a chromosome

The interesting thing about it is that the viral protein attaches to what is called the fragile spot on the chromosome. There, DNA is particularly susceptible to damage, mutations, and breaks during cell division. “These spots tend to crack when subjected to additional stress,” Lee and her colleagues explain. Their analyzes aptly revealed that docking to the viral EBNA1 protein breaks the DNA strand at this point.

“We therefore suspect that accumulation of EBNA1 at this already unstable site could cause a chromosome break at position 11q23,” the researchers write. This was confirmed in cell division of infected cells: “About 40 percent of mitotic cells have one or more chromosomes that appear to be broken at the EBNA1 docking site.” This discontinuity in the eleventh chromosome was also retained in subsequent cell divisions.

“We have thus discovered a previously unrecognized relationship between EBV and changes in the eleventh chromosome,” Lee and her colleagues say. The experiment shows for the first time how a viral protein breaks through a fragile point in the genome.

Chromosomal damage can also be detected in tumor data

This damage to DNA is one of the factors that can lead to cell degeneration and, consequently, cancer. To check if this was also the case with a chromosome break caused by an Epstein-Barr virus protein, the researchers then looked for signs of this break in the DNA sequences of cancer tumors.

Analysis of genome data for 2,439 tumor types and 38 types of cancer revealed: “The carcinoid tumors of patients with latent EBV infection had significantly more abnormalities in chromosome 11 than the EBV-positive ear and throat tumors contained alterations in chromosome 11,” Lee and her team report.

An opportunity for early detection and prevention

According to the researchers, this may explain why latent infection with Epstein-Barr virus, and especially resurgence of this virus, increases the risk of developing certain types of cancer. “We hypothesize that reactivation of the virus in infected cells leads to breakage of the eleventh chromosome by the viral EBNA1 protein,” the team explains. The risk of such genetic damage increases, the more copies of the viral docking sequence a person carries at that genome position. This explains why not everyone infected with EBV will develop cancer.

“This discovery opens up the possibility of specifically screening people for this risk factor for EBV-related diseases,” says senior author Don Cleveland of the University of California, Berkeley. “Furthermore, this could be used to prevent the emergence of such diseases by preventing the binding of EBNA1 to these genetic sequences.” (Nature, 2023; doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05923-x)

Cowell: University of California – San Diego